The auto de fé

After having fallen into the hands of the Inquisition, the accused had to take part in the ceremony that allowed their reintegration into Catholic society, the auto de fé, the act of faith, a public procession that culminated in a devoted spectacle and often, in the sixteenth century and the first half of the seventeenth century, in a pyre. It was very difficult to avoid the auto de fé: the Franciscan tertiary Francisca Spitaleri, under investigation as a witch and seer, as well as a follower of the alumbradismo, isolated in a room near the apartments of the alcalde – the captain of the castle – tried to descend from a window using knotted sheets on 9 June 1622. She was found the next morning smashed on the pavement, because the improvised rope gave out.

Since the institution of the Inquisition until its dissolution 114 autos were celebrated in Sicily, most of which in Palermo. This was the first time in which those who had been captured could meet their loved ones, who for weeks, sometimes for months, had not known anything about them. On the occasion of the auto de fé, the capital was full of people eager to watch the show and to find out what had happened to their relatives who had fallen into the hands of the inquisitors.

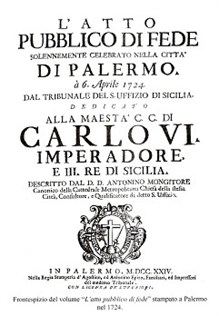

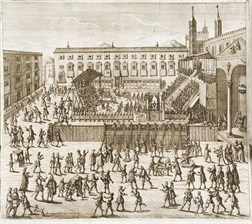

In the entrance hall of the Steri Palace, the investigated were prepared: with their own money what was necessary to pack the sambenito, a yellow – the colour of infamy – scapular and a mitre had been bought. As already painted on the sambenito, you could know which was the fate of the prisoner: who bore the cross of Saint Andrew was probably reconciled; who carried the flame pointing down was penitenziato; those with flames upward were released to the secular arm. Many autos de fé were very carefully described. An accurate description of one of the last events of sombre splendor of the Inqusition in the island was immediately given to the press, L’atto pubblico di fede solennemente celebrato nella città di Palermo a 6 aprile 1724 dal Tribunale del S. Uffizio di Sicilia, whose author was the canon Antonino Mongitore. The work was commissioned by the inquisitors to the only man who seemed, at that moment in Palermo, the writer more convinced of the goodness of methods that then, even in Catholic circles, appeared outdated and counterproductive. Eager to show all his zeal, Mongitore meticulously describes the procession that left the Steri Palace to cover the Cassaro and reach the Cathedral. The procession was opened by the green veiled cross of the Inquisition, followed by familiars and the Society of the Assumption (the brotherhood linked to the Inquisition where there were many aristocrats), then the inquisitors riding along with all the employees of the tribunal, finally halberdiers, drummers and pipers, municipal and royal officials, congregations and Religious Orders. At the center, «le persone processate in numero di ventotto, ad una ad una, con abito giallo e candela di cera gialla estinta in mano […] con vergognose mitre sul capo, nelle quali erano rozzamente dipinte l’enormità commesse, e i due Pertinaci [suor Geltrude Cordovana and fra Romualdo di S. Agostino]». The procession crossed the city full of onlookers, familiars of the Inquisition arrived from all parts of Sicily, to get under the windows of the archbishop’s palace, where he awaited the viceroy and where the stands were mounted.

In the entrance hall of the Steri Palace, the investigated were prepared: with their own money what was necessary to pack the sambenito, a yellow – the colour of infamy – scapular and a mitre had been bought. As already painted on the sambenito, you could know which was the fate of the prisoner: who bore the cross of Saint Andrew was probably reconciled; who carried the flame pointing down was penitenziato; those with flames upward were released to the secular arm. Many autos de fé were very carefully described. An accurate description of one of the last events of sombre splendor of the Inqusition in the island was immediately given to the press, L’atto pubblico di fede solennemente celebrato nella città di Palermo a 6 aprile 1724 dal Tribunale del S. Uffizio di Sicilia, whose author was the canon Antonino Mongitore. The work was commissioned by the inquisitors to the only man who seemed, at that moment in Palermo, the writer more convinced of the goodness of methods that then, even in Catholic circles, appeared outdated and counterproductive. Eager to show all his zeal, Mongitore meticulously describes the procession that left the Steri Palace to cover the Cassaro and reach the Cathedral. The procession was opened by the green veiled cross of the Inquisition, followed by familiars and the Society of the Assumption (the brotherhood linked to the Inquisition where there were many aristocrats), then the inquisitors riding along with all the employees of the tribunal, finally halberdiers, drummers and pipers, municipal and royal officials, congregations and Religious Orders. At the center, «le persone processate in numero di ventotto, ad una ad una, con abito giallo e candela di cera gialla estinta in mano […] con vergognose mitre sul capo, nelle quali erano rozzamente dipinte l’enormità commesse, e i due Pertinaci [suor Geltrude Cordovana and fra Romualdo di S. Agostino]». The procession crossed the city full of onlookers, familiars of the Inquisition arrived from all parts of Sicily, to get under the windows of the archbishop’s palace, where he awaited the viceroy and where the stands were mounted.

In the cathedral square, the sentences were read. So not only the reputation of the individual was permanently ruined, but shame also marked their heirs, who could not exercise for four generations public and ecclesiastical offices or particular professions, nor enjoy privileges such as wearing jewelry, ride horses or bear arms. The story of Mongitore is awesome: while the sentences were read, the people left their seats and took refuge in the lower part of the stands, where they began to feast on lavish refreshments prepared for the occasion. So no one listened to the sentence of release to the secular arm of Sister Gertrude and fra Romualdo, nor the immediate ratification of their death sentence.

In the cathedral square, the sentences were read. So not only the reputation of the individual was permanently ruined, but shame also marked their heirs, who could not exercise for four generations public and ecclesiastical offices or particular professions, nor enjoy privileges such as wearing jewelry, ride horses or bear arms. The story of Mongitore is awesome: while the sentences were read, the people left their seats and took refuge in the lower part of the stands, where they began to feast on lavish refreshments prepared for the occasion. So no one listened to the sentence of release to the secular arm of Sister Gertrude and fra Romualdo, nor the immediate ratification of their death sentence.

At the end of the banquet, at night, in the light of the torches, the procession moved towards the walls, on the plain of St. Erasmus. Here, the two unfortunate «[…] con gli abiti del loro ordine, e con sopravveste intonacata di pece, dipinta a fiamme, e con mitre vituperose pur delineate con fiamme» were burned alive: with them, the total number of the condemned to death by the Sicilian Inquisition became 265. A horrible sight, which – ironically – thanks to the writing of Mongitore, was well known and condemned in a Europe that, in the early eighteenth century, no longer tolerated the religious burnings.

At the end of the banquet, at night, in the light of the torches, the procession moved towards the walls, on the plain of St. Erasmus. Here, the two unfortunate «[…] con gli abiti del loro ordine, e con sopravveste intonacata di pece, dipinta a fiamme, e con mitre vituperose pur delineate con fiamme» were burned alive: with them, the total number of the condemned to death by the Sicilian Inquisition became 265. A horrible sight, which – ironically – thanks to the writing of Mongitore, was well known and condemned in a Europe that, in the early eighteenth century, no longer tolerated the religious burnings.