Extraordinary testimonies

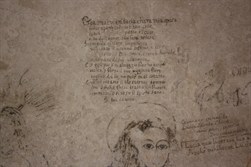

A veritable phantasmagoria, where designs alternate with the words, covers every inch of the walls of these rooms: poor marks, made with egg white mixed with the dust of broken tiles or floor to ashes, but extremely meaningful and valid to reconstruct, albeit in an inevitably approximate manner, the suffering of those who passed here. The warning that we can read in a corner is very eloquent:

A veritable phantasmagoria, where designs alternate with the words, covers every inch of the walls of these rooms: poor marks, made with egg white mixed with the dust of broken tiles or floor to ashes, but extremely meaningful and valid to reconstruct, albeit in an inevitably approximate manner, the suffering of those who passed here. The warning that we can read in a corner is very eloquent:

Nixiti di spiranza vui ch’intrati (Abandon all hope you who enter here)

It is a quotation from Dante, which well defines the atmosphere that a prisoner had to breathe within these walls. Pitrè had already traced the tragic words:

Averti ca ccà si duna la corda.

Statti in cervellu ca ccà dunanu la tortura.

And more:

V’avertu ca ccà prima dunanu corda…

Statti in cervelli ca cca dunanu la tortura

arti infami.

It is a message sent by a prisoner to those who came later, and that reveals, perhaps more eloquently than anything else, the sad reality of the Inquisition. But on the walls of the cells, a hand written note reminds that, despite the suffering:

Semper tacui (I never talked).

“I never talked, never admitted my guilt”. Through their designs, we can delineate the identity of the prisoners. Here we see a monster that swallows the characters of the Old Testament kneeling in front of the figure of Christ: it is a possible evidence of Judaizing heretics passed between these walls. The Jews were expelled from the domains of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon in 1492; many of them, however, converted to Catholicism. Sometimes these conversions were false, in secret many continued to profess their faith. But other times they only perpetuated old habits: they did not eat pork or meat dishes that mixed with milk or dairy products; if they worked on Saturday they wore clean clothes; women washed themselves after the monthly rules, and so on: this was seen by the inquisitors as an unequivocal signal of heresy. They were the first victims of the inquisitors: 23 were acquitted, 570 were “reconciled”, 1046 were penitenziati (subjected to a penance), 195 were burned in person and 276 burned in effigy (a statue was burned when the accused was dead or had escaped).

“I never talked, never admitted my guilt”. Through their designs, we can delineate the identity of the prisoners. Here we see a monster that swallows the characters of the Old Testament kneeling in front of the figure of Christ: it is a possible evidence of Judaizing heretics passed between these walls. The Jews were expelled from the domains of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon in 1492; many of them, however, converted to Catholicism. Sometimes these conversions were false, in secret many continued to profess their faith. But other times they only perpetuated old habits: they did not eat pork or meat dishes that mixed with milk or dairy products; if they worked on Saturday they wore clean clothes; women washed themselves after the monthly rules, and so on: this was seen by the inquisitors as an unequivocal signal of heresy. They were the first victims of the inquisitors: 23 were acquitted, 570 were “reconciled”, 1046 were penitenziati (subjected to a penance), 195 were burned in person and 276 burned in effigy (a statue was burned when the accused was dead or had escaped).

The recurrent sacred images described a deeply devout humanity, but incapable of a faith that was free from superstitious forms: the aloud recommendation to saints and martyrs or the request for special graces could catch the inquisitors’ attention. Unfortunately, these formulas were fully included in the religious traditions of Sicily.

The recurrent sacred images described a deeply devout humanity, but incapable of a faith that was free from superstitious forms: the aloud recommendation to saints and martyrs or the request for special graces could catch the inquisitors’ attention. Unfortunately, these formulas were fully included in the religious traditions of Sicily.

The penalties for alleged witches and wizards, considered able to operate through spells and potions, were more serious. But also the situation of healers and midwives was very difficult: they were often accused of having contacts with the world beyond because the remedies they proposed to patients were often accompanied with litanies and prayers. It made them easy victims.

There were also priests and nuns among the accused, sometimes for heresy but also for immoral costumes (such as married priests or priests who took advantage of their position and the seal of the confessional to sollicitare ad turpia).

There were also priests and nuns among the accused, sometimes for heresy but also for immoral costumes (such as married priests or priests who took advantage of their position and the seal of the confessional to sollicitare ad turpia).

The islanders who had embraced the Lutheran or Calvinist faith and the foreigners who had moved to Sicily to preach the reformed creed were considered bearers of a religion condemned with the maximum penalty by the inquisitors. An inscription in English reminds us of these presences and the strong dissent against the Catholic religion in Sicily, as in the rest of the Italian peninsula, cultivated between the sixteenth and seventeenth century.

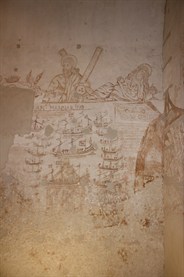

Other convicts who risked serious penalties were the renegades, those who – by virtue of their maritime employment or the fact that they had been abducted during coastal raids by the Barbary pirates when they were young – had converted to Islam, finding, however, in the Muslim world possibilities of social ascent absolutely unprecedented in the environment from which they came. In the Ottoman Empire many public offices were open to the converted people, while the exercise of piracy – practiced by people who knew the Italian coasts – ensured enormous wealth. Captured during raids and naval enterprises, these people were judged by the inquisitors. The testimony of the passage in the rooms of the Steri Palace of one of these figures, Francesco Mannarino, is magnificent, from a purely artistic point of view: he is the author of a splendid representation of the Battle of LepantoWas a naval battle that took place on 7 October, 1571 and that pitted the Holy League (Spanish Monarchy, the Duchy of Savoy, the Papacy and the Republics of Venice and Genoa) against the Ottoman Empire. The victory put a stop to Ottoman expansion in the Christian West. drawn in a few months, from January to May of 1600. Fortunately, since the second half of the sixteenth century renegades who confessed that they had converted to Islam in order to save their life were no longer condemned to serious penalties.

Other convicts who risked serious penalties were the renegades, those who – by virtue of their maritime employment or the fact that they had been abducted during coastal raids by the Barbary pirates when they were young – had converted to Islam, finding, however, in the Muslim world possibilities of social ascent absolutely unprecedented in the environment from which they came. In the Ottoman Empire many public offices were open to the converted people, while the exercise of piracy – practiced by people who knew the Italian coasts – ensured enormous wealth. Captured during raids and naval enterprises, these people were judged by the inquisitors. The testimony of the passage in the rooms of the Steri Palace of one of these figures, Francesco Mannarino, is magnificent, from a purely artistic point of view: he is the author of a splendid representation of the Battle of LepantoWas a naval battle that took place on 7 October, 1571 and that pitted the Holy League (Spanish Monarchy, the Duchy of Savoy, the Papacy and the Republics of Venice and Genoa) against the Ottoman Empire. The victory put a stop to Ottoman expansion in the Christian West. drawn in a few months, from January to May of 1600. Fortunately, since the second half of the sixteenth century renegades who confessed that they had converted to Islam in order to save their life were no longer condemned to serious penalties.