The investigations of the Inquisition and the role of the “familiars”

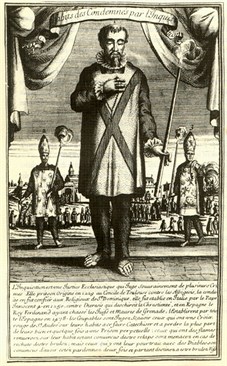

The first event of the Inquisitorial process was the public proclamation of the general Sermon or Edictum fidei. More or less every year, the inquisitors, in agreement with the bishop of Palermo, issued for the whole island a notice inviting any person who knew or had even a suspicion of heresy against someone to report it to the tribunal. During the seventeenth century, however, the notice included also common sins that had little to do with the theological disquisitions. In addition to the apostates – those who had renounced the Catholic faith to embrace another – alleged witches and wizards, healers, midwives, bigamous, sodomites, but also blasphemers, perjurers, and many others were pursued. The sins of these men could be judged and forgiven after repentance, by any priest. In vain the improper interference by the Inquisition in the traditional ecclesiastical action was publicly underlined: eager to extend their range, the inquisitors arrogated to themselves the right to judge even what did not seem to be considered as a crime of heresy.

The first event of the Inquisitorial process was the public proclamation of the general Sermon or Edictum fidei. More or less every year, the inquisitors, in agreement with the bishop of Palermo, issued for the whole island a notice inviting any person who knew or had even a suspicion of heresy against someone to report it to the tribunal. During the seventeenth century, however, the notice included also common sins that had little to do with the theological disquisitions. In addition to the apostates – those who had renounced the Catholic faith to embrace another – alleged witches and wizards, healers, midwives, bigamous, sodomites, but also blasphemers, perjurers, and many others were pursued. The sins of these men could be judged and forgiven after repentance, by any priest. In vain the improper interference by the Inquisition in the traditional ecclesiastical action was publicly underlined: eager to extend their range, the inquisitors arrogated to themselves the right to judge even what did not seem to be considered as a crime of heresy.

Generally, the notice fixed to six days after its promulgation the deadline for complaints, explaining that “those who do not denounce are not excusable and will be punished harshly”. The informers could take advantage of the Steri’s side entrance, in order not to be seen and to keep the secret of their identity, that was never revealed to anyone and especially to the accused.

Through the first denunciations, inquisitors formed a list of suspects; then, they proceeded to identify the witnesses, even if just one person could be sufficient. Relatives, friends, neighbors, employers were approached by descreet people questioning them warily about the person under investigation. These descreet people were the so-called “familiars”, men and women secretly in the service of the tribunal which used them to collect information. Until 1546 these were generally people of low condition, because the Sicilian nobles and patricians opposed the settlement of the tribunal on the island and took part in the revolts against it. After 1543, however, there was a different behaviour in a large sector of the ruling classes in Sicily. If previously they had shared the arguments of the Neapolitan barons against the introduction of the Inquisition in the kingdom, in the aftermath of the renewal of the tribunal’s privileges they were quick to become officers and familiars, so escaping the ordinary condition of the subjects of secular political authority and acquiring that of subjects of the Inquisition. They tried to be a part of the institution that not only began to have a precise control over the entire territory of the island, but that was also, by virtue of its top-down structure, a valuable link with the court of Madrid. Furthermore, being officials of the tribunal or familiars gave some privileged conditions. Familiars, although they were not paid for tasks that could be very harsh, had in fact a number of prerogatives and privileges: tax exemptions, right to carry a weapon (a faculty extensible, and extended, to relatives and servants) and to be judged by the tribunal of the Inquisition also for common crimes. In a society where the law was unequal to everyone and where everyone, according to his social position, could be judged by a different tribunal – only in Sicily there were more than fifty – the Inquisition gave familiars the possibility of enjoying a privileged juridical position.