Treaties and cookbooks

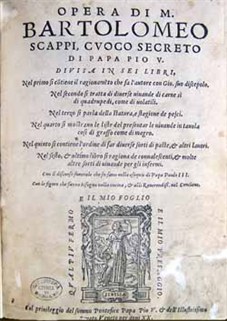

The culinary passion, the pursuit of taste and greater indulgence in the sin of the gluttony, all these elements that characterized the European culture of the Early modern age, and in particular of the Baroque period, were the basis of a rich and varied production of works focused on cuisine and the art of cooking. The first treaties to deal with cuisine were written by professional chefs and therefore were defined as technical and non-literary texts, appearing in Europe in the last centuries of the Middle Ages. The fourteenth century Opusculum de saporibus by the Milanese physician Maino Maineri is a famous example of a technical book that also treated dealt with diet and provided recipes. The spread of printing allowed for a wider circulation of similar texts, among which we can mention: the works of Maestro Martino da Como (Libro de arte coquinaria, fifteenth century), Cristoforo di Messisbugo (Banchetti composizioni di vivande e apparecchio generale and the Libro novo nel qual si insegna a far d’ogni sorte di vivanda sixteenth-century), Bartolomeo Scappi (a treatise on cuisine divided into six books and published in 1570, image) and Vittorio Lancellotti (Lo scalco prattico, 1627). The cookbooks were spread across the continent during the seventeenth century, witnessing, and at the same time enshrining, the supremacy of various national cuisines: Italian in the sixteenth century, Spanish between the sixteenth and seventeenth century and French in the second half of the seventeenth century, to which the greatest number of works and treaties was dedicated.

The culinary passion, the pursuit of taste and greater indulgence in the sin of the gluttony, all these elements that characterized the European culture of the Early modern age, and in particular of the Baroque period, were the basis of a rich and varied production of works focused on cuisine and the art of cooking. The first treaties to deal with cuisine were written by professional chefs and therefore were defined as technical and non-literary texts, appearing in Europe in the last centuries of the Middle Ages. The fourteenth century Opusculum de saporibus by the Milanese physician Maino Maineri is a famous example of a technical book that also treated dealt with diet and provided recipes. The spread of printing allowed for a wider circulation of similar texts, among which we can mention: the works of Maestro Martino da Como (Libro de arte coquinaria, fifteenth century), Cristoforo di Messisbugo (Banchetti composizioni di vivande e apparecchio generale and the Libro novo nel qual si insegna a far d’ogni sorte di vivanda sixteenth-century), Bartolomeo Scappi (a treatise on cuisine divided into six books and published in 1570, image) and Vittorio Lancellotti (Lo scalco prattico, 1627). The cookbooks were spread across the continent during the seventeenth century, witnessing, and at the same time enshrining, the supremacy of various national cuisines: Italian in the sixteenth century, Spanish between the sixteenth and seventeenth century and French in the second half of the seventeenth century, to which the greatest number of works and treaties was dedicated.

In addition to these cookbooks and recipes, another types of texts were composed on the theme of food and culinary culture. De honesta voluptate, by the humanist Bartolomeo Sacchi, called il Platina constituted a European model for all the literature that sought to defend and celebrate good food, delicacies and even gluttony and drinking. A simple but elegant cuisine, which respected the original flavours of the food without covering them with spices and seasonings, was the goal to be attained and described by a large group of “amateurs” in the kitchen, such as aristocrats, clergymen and travelers, fueling a veritable patronage of the culinary arts. The “collections of secrets” were rather works of a mixed nature, i.e. that dealt with medicine and cosmetics but also ended up supplying recipes for the manufacturing of products then considered essential for body care and beauty, such as jams, preserves and syrups. Numerous treaties flourished relating to the various people who worked in kitchens and banquets, as butlers, sommeliers or waiters, while many literary works, from RabelaisFrançois Rabelais (1494-1553) was a writer and humanist, one of the most famous exponents of the French Renaissance. Pantagruel and Gargantua are his most famous works. Often the victim of censorship and repeatedly listed in the Index of Forbidden Books, Rabelais was an author who distinguished himself by verbal creativity, that is he did not choose the “high genres” of the Petrarchan lyric or chivalric epics, but preferred “low” topics such as food, wine and sex.‘ Gargantua and Pantagruel onwards, celebrated the pleasures of good food and good wine, the joy and conviviality of taverns and banquets, following, in this sense, a rich medieval tradition. The Bacchanalian societies, which spread to a large part of Europe, was further confirmation, with its mix of games, food, wine and orgies, of the festive and unbridled spirit that affected some sectors of European society in the Early Modern age.